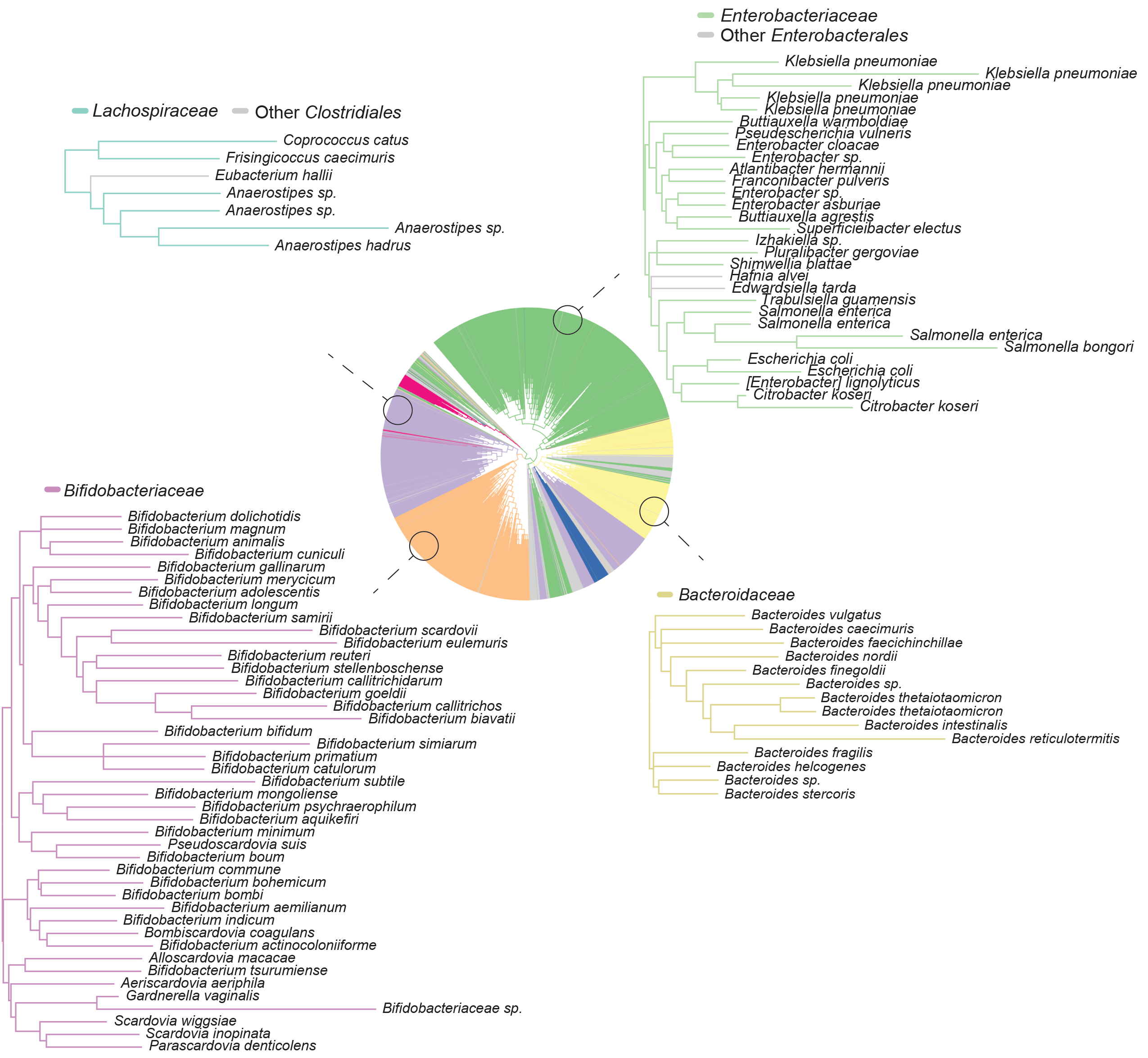

Subspecies phylogeny in the human gut revealed by co-evolutionary constraints across the bacterial kingdom

With the advent of sequencing, biological systems like bacteria can be described in a myriad of ways, including by their entire genome sequence. But, with this capacity comes a conundrum.

Do we actually use the whole genome to describe a bacterial strain? Should we throw away a lot of the genomic information and only focus on a subset of the genome? In other words, at what resolution is it useful to describe a strain to both categorize and functionally characterize it? This paper deals with this problem head on and shows a central result: using constraints across evolution that are learned directly from phylogenetic data is a far more useful way of describing strains both in regard to (i) categorization and (ii) functional capacity of strains. We show here that strain-level differences amongst bacteria of the same species can be effectively distinguished by taking into account the evolutionary context—a finding that enables understanding the extent of strain-level differences amongst bacterial communities residing within humans. Using the human gut microbiome as a model system, we show that strain-level differences that reside below the level of species cluster by classes of donors where classes are related to a previous history of phage infection. We then go on to show that strain-level metabolism can be directly predicted from the evolutionary-based description of strains rather than their genome sequence. This work lays the foundation for creating interpretable latent spaces of evolved systems—a theoretical framework that has fueled much progress and projects in our laboratory.